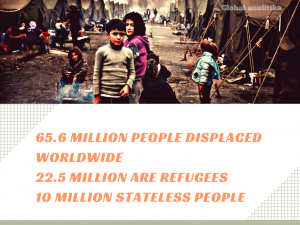

In 2015, the number of people applying for asylum in the EU peaked at 1.26 million to trigger the current migration crisis, while over 2,257 people are thought to have lost their lives in the Mediterranean in the first six months of 2017 alone (as of 28 June 2017). In 2016 5,022 lives were estimated to be lost in the Mediterranean and in 2015 3,771.

In 2015 and 2016 alone, more than 2.5 million people applied for asylum in the EU. Authorities in the member states issued 593,000 first instance asylum decisions in 2015 – over half of them positive. Frontex, the EU border surveillance agency, collects data on illegal crossings of the EU’s external borders registered by national authorities. In 2015 and 2016, more than 2.3 million illegal crossings were detected. Migration has been an EU priority for years. Several measures have been taken to manage the crisis as well as to improve the asylum system. According to the 2017 Eurobarometer poll, 73% of Europeans still want the EU to do more to manage the situation. Migration was also seen to be a top priority in the 2016 Eurobarometer survey results, EUROPARL reports.

Anti-immigration sentiment has risen across Europe in recent years, and the current migrant crisis in Europe is divided public opinion with many former opponents of migration that changed after seeing the disturbing images in the media of children and adults who have died on the way to Europe.

- Migrant crisis and economic benefits

While migrants can help boost labor, there is fear among the more cautious observers of the migrant crisis in Europe that many migrants coming from the Middle East and Africa are not qualified or educated, and can therefore burden and exert additional pressure on government finances.

The anti-immigration groups argue that migrants’ influx will lead to further pressure on public services, such as health care, housing and education systems. Others argue that net migration (immigration minus emigration) tends to offer more benefits than shortcomings with higher tax revenue from immigrant workers.

The atmosphere that creates negative attitudes towards migrants is not only present in Europe, but also in America. Thus, Donald Trump’s decision, which divides the American public, on the prohibition of travel for citizens of several major Muslim countries has sparked debate not only on the security implications of immigration, but also on its economic impact.

A new working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research shows refugees provide a net contribution to the economy through the taxes they pay over time, countering the notion that they are a drag on the economy due to a reliance on social benefits, Bussines Insider reports.

Trump’s ban initially faced stiff legal challenges, but was later upheld by the Supreme Court for a narrower group of immigrants. Under Trump’s plan, the maximum number of refugees allowed into the US in fiscal 2017 will likely decline from 110,000 to 50,000, according to Pew Research. About 3 million refugees have been resettled in the US since Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980, Pew estimates.

The report from Notre Dame economists William Evans and Daniel Fitzgerald finds that “over their first 20 years in the United States, refugees who arrived as adults aged 18-45 contributed more in taxes than they received in relocation benefits and other public assistance.” The Notre Dame study drew on State Department data to create a sample of 20,000 refugees who entered the country between 1990 and 2014. The authors also find that “the younger the refugees were when they resettled in America, the more likely they were to catch up with their native-born peers educationally and economically.”

The research also found that refugees who arrived before the age of 14 had, by ages 19-24, graduated from high school at the same rates as American youth. By ages 23-28, those refugees displayed the same college graduation rates as the US-born population.

“Refugees who arrived as children of any age have much higher school enrollment rates than U.S.-born respondents of the same age,” the research finds.

The US spends an average of $15,148 in relocation costs and $92,217 in social benefits over an adult refugee’s first 20 years here, the NBER said, citing the Notre Dame report. Over that period, the average adult refugee pays $128,689 in taxes — $21,324 more than the benefits received.

And that’s just the economics of it. Trump’s case for a “Muslim-ban” during the campaign centered on fears of crime and terrorism. But here too, there is ample evidence such concerns are unfounded.

Some people see this migrant crisis as a humanitarian crisis, and others consider it as challenge or a threat, while economists have a completely different approach. Economists tend to see a large influx of refugees not as an obligation or threat – but as an opportunity. In particular, Europe faces major demographic challenges, the population is old, and in many countries it is decreasing, since people are also leaving those countries. Last year, the mortality rate was higher than the birth rate in Greece and Italy (where the vast majority of migrants came), and also in Germany (where most migrants arrived). German economy creates faster jobs than domestic residents can fill them up. Obviously, the answer is obvious – Europe should not only accept refugees, but also welcome the last increase in labor force. As Thomas Piketty, the celebrated author of “Capital in the 21st Century,” recently wrote, the crisis represents an “opportunity for Europeans to jump-start the continent’s economy.”

- France wants to contribute to solving the migrant crisis

Europe’s ‘big four’ continental powers will attend a summit hosted by French President Emmanuel Macron, aimed at getting Europe’s migrant crisis under control. Macron has also invited three African nations to the talks.

Diplomats said today’s summit, which will host Germany, Italy and Spain as well as the leaders of Chad, Niger and Libya, aimed to assess the situation.

European countries are wondering how to deal with the arrival of hundreds of thousands of people fleeing war, poverty and political upheaval in the Middle East and Africa.